X Marks the Spot of a Bull Market in Distress

Let me introduce Company X, a U.S. based firm with a market cap of $166B, and a long history as a listed security trading since 1981. Long-term investors holding this paper in their portfolios will have experienced the inevitable rough patch here and there, but on all accounts Company X is a fine representative of corporate America. It operates in the consumer discretionary sector, and has performed extraordinarily since the crisis in 2008. The stock price is up 670% since the first quarter of 2009—compared to about 140% for the S&P 500—and investors have even been able to enjoy a steadily rising dividend.

I recently had a go at the perma-bears, and promised that I would reciprocate by taking aim at the perma-bulls. The discussion of Company X's fortunes just does that.

The firm is a perfect example of the dynamics which have driven the bull market in U.S. equities since the crisis. But for all its merits, Company X's experience in this cycle and the decisions by its management tell a cautionary tale. I am no stock picker, but I know how to read an income statement and balance sheet, and even a cursory glance at this firm raises alarm bells. If my spider sense is triggered by looking through the entrails of this company, it naturally forces me to raise question on the bull market itself.

But let's start with the positives*.

Company X's revenue growth recovered strongly following the crisis, and has outpaced nominal U.S. GDP growth since 2011. The market's estimate—combined with my forecast for nominal GDP growth in Q4—indicate the rise in turnover will match economic growth this year. GDP beating revenue growth is a crude measure of success, but it shows that Company X has been doing something right. In particular, it indicates that its market share has risen, which is a good starting point.

Margins have also expanded—doubling from a low of 6.1% in 2009 to 13.2% this year—providing evidence of solid cost management. The less positive narrative is that higher margins are entirely cyclical, but I am willing to give Company X the benefit of the doubt. In the ten years I have data for, Company X has consistently managed to increase revenues faster than costs, and in the 2008/09 recession variable costs were reduced more than the decline in turnover. In a world where margins of consumer facing companies are being squeezed by secular trends, Company X has managed to buck the trend.

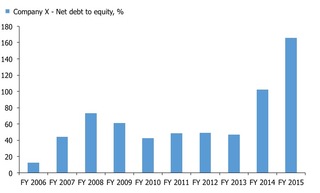

So far so good then; Company X's income statement gives it a conditional pass. A look at the balance sheet, though, likely will make investors more careful, if not running for the hills. The firm's treasury and managment have undoubtedly been spurred by powerful incentives and shareholder pressure, but the costs look unpalatable. A few carefully selected data tell the key story. From 2005 to 2014, shares outstanding fell 40% to $1.3B, and long term debt rose six-fold from $2.3B to $16B, with the inevitable result that net-debt-to-equity swelled to an eye-watering 170%, up significantly from a lowly 12% in 2006.

The arithmetic boost to earnings-per-share has been impressive, and on current trends the reduction of shares via buybacks will end up being responsible for almost 40% of total EPS this year. The latest annual balance sheet shows a total treasury stock—own shares held by the company—of $26.2B, almost equivalent to, and essentially offsetting, retained earnings worth $B27.

Investors who haven't been living in a cave since 2009 will recognise these figures as representative of a larger trend. It is difficult to give exact data on this phenomenon, but non-financial corporates have been on a credit binge in recent years, and the proceeds has mainly been used to finance shareholder treats in the form of buybacks and dividends. A Reuters study of 3,297 publicly traded non-financial companies indicate, incredibly, that share buybacks and dividends now exceed net income. In the second quarter, $58B in new debt issuance by S&P 500 constituents was earmarked for stock buybacks, the largest such figure ever recorded.

A trend of this nature and with such persistence can only exist if fuelled by both supply and demand side factors. On the supply side, debt-financed financial engineering to boost dividends and stock buybacks have no doubt resonated with corporate treasurers due to low interest rates. The post-crisis monetary policy regime has reduced the cost of capital and allowed firms to term out their liabilities. But this would not have been possible without an eager demand side, arguably providing the proverbial spark to ignite the bonfire. In a world starved of yield due to ZIRP and QE, investors have found the combination of long-dated corporate bond issuance and debt financed handouts via buybacks and dividends the perfect remedy to low interest rates. So far, they have piled into the trade with little care for what might happen when the tide turns.

Earlier this year, proponents of this "trade" celebrated as the Fed opted to postpone a much awaited rate hike, but like peeing your pants to stay warm, the comfort was short lived. The Fed finally pushed the button this month, raising rates by 25 basis points, and signalled that further hikes are likely in the next 12 months. A levered balance sheet makes sense in a world of low interest rates—it reduces the cost of capital—but it leaves you vulnerable when the tide turns and rates rise. Company X has been a poster-child for the trend described above, and its shareholders likely would love to know whether the days of debt-financed financial engineering has come to an end.

Cash on hand and free cash flow, though, means servicing your debt—and perhaps even paying a dividend—should not be a problem. Defenders of Company X likely would point out that $15B in current assets provide a decent cushion. $11B of this is inventories, however, and given the nature of the business in which Company X operates, I am confident these will not fetch book value in a situation where "emergency cash" is needed.

A free cash flow analysis, however, restores the bull case somewhat. Company X is a strong cash generator, and even assuming zero cash from debt issuance, dividends and share buybacks looks just about coverable from operating income**. But it won't take much cyclical headwind for Company X's cash generating machine to falter, and with it—one has to assume—its share price.

Company X's debt rollover schedule looks manageable although a $3B 10-year 5.4% CP bond maturing in March looks interesting. The firm should be able to cover the redemption through cash flow—unless the economy falls off a cliff in Q1—but it could also choose to re-finance despite having to do so in environment where credit spreads are widening. Overall though, the firm's treasury has been smart, and taken advantage of investor appetite for duration to term out its debt. Company X has bond principal outstanding of $20.3B with a weighted year-to-maturity of a comfortable 13.5 years. Apart from the $3B bond noted above, debt maturing from 2017 to 2019 is a manageable $2.6B.

What's more, most of its bonds are callable which means the firm has the option to redeem should cash flow allow it. If it chooses to do so, though, it likely will threaten the generous buyback and dividend scheme, and so also threaten its share price. But the bottom line is that the firm does not look like a bankruptcy candidate.

None of the information above will deter the bulls and nor should it necessarily. Investors should be ready to invest in a good cash generator—even if levered—at the right price. But herein lies the rub.

Fair value, like beauty, lies in the eye of the beholder, and I will let my readers pass judgement on the chart above for themselves. A price-to-sales ratio of 2 is expensive based on the firm's most recent history, but it is far from the multiple commanded during the craziness of 1999. The price-to-book ratio, however, looks outright scary, and is the result of an erstwhile good balance sheet being dragged through the mud to cater for buyback and dividend hungry investors. A turning point in the hunt for debt-financed cash flows and a more demanding look at leverage will be a damaging cocktail for Company X's shareholders and management.

Bulls still have momentum on their side with Company X, however, and I have little opinion on the immediate future of its share price. But its surge since 2009, and the drivers of its performance are representative of a trend which can't, and won't go on forever.

When the rubber finally hits the road, evaporating corporate bond market liquidity, one-sided investor positioning and nosebleed equity valuations will not only be a painful cocktail for credit markets, but also for Company X and its brethren. When history is written on this business cycle, journalists and historians will describe how monetary policy gave rise to a diabolical fusion between yield starved investors and the siren song of a lower cost of capital and shareholder satisfaction for corporate treasurers. I cannot say when we will get to write that epilogue, but the carcasses will be left to stink for a long time.

In five years I venture that we will be looking back at Company X and its ilk shaking our heads in disbelief. It will be the same as thinking back to the heyday of the subprime mortgage carousel, where prostitutes were given a mortgage with no down-payment to purchase a third house in the middle of the desert. I imagine them sitting down with their mortgage advisor, looking at a grid of the local area. "I want that one" they would say, eagerly marking down a property on the map; "X marks the spot." It always does.

--

* Click on charts for better viewing.

** The slightly more bearish slant is that Company X has been devoting way too much of its cash flow to pay dividends and retire shares—and too little reinvestment into the business—but from an accounting perspective top line cash generation is solid.