The BOJ & JPY and some new predictions on global fertility

I have a few things on my mind this week. We have to talk about Japan and the BOJ. Last week’s decision by the BOJ to raise its deposit rate above zero for the first time in 17 years cements Japan and its central bank as a counter cyclical indicator, of sorts. While major central banks have spent the majority of the past 18 months raising interest rates, the BOJ has stubbornly resisted calls to exit NIRP, despite rising inflation. Now that the ECB, BOE and Fed are on the cusp of lowering interest rates, the BOJ is pulling the trigger on a hike. The BOJ’s decision raises a number of fundamental questions for global macro traders and thinkers. The most obvious one is whether the twin inflation shock from Covid and shifting geopolitics is now pulling developed rate markets out of their ZIRP/NIRP funk. And if they are, does this mean that the idea of long-term gravity of rapidly ageing population weighing on inflation and interest rates is wrong? Is Japanification now reversing? I am sceptical, but if Japan manages to escape, it would go a long way to falsify the idea of a determinist link between ageing and disinflation.

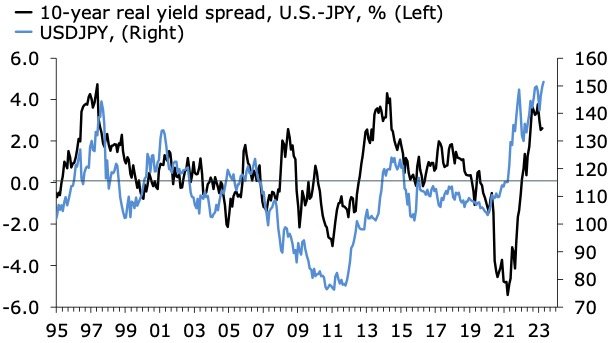

Before we get to that, the most eye-catching consequence of policy divergence between the BOJ and the other majors has been a big move in the Yen. USDJPY has soared to just over 150, as US bond yields have left JGB yields for dead on the back of significant hikes in the US and inactivity by part of the BOJ. We’ve seen similar moves in EURJPY and GBPJPY. Surely, this will now reverse? The initial vote from markets is that JPY weakness is unlikely to be seriously challenged by the BOJ’s move.

Investors are betting that while the rate differential is now narrowing between the JPY and USD, it will remain wide , supporting a sustained carry position in USD, and just about everything else, funded in JPY. Markets have pulled back expectations for Fed rate cuts in the past few months, and few believe that the BOJ will get far above zero. Can you blame them? The first chart below shows that Japanese inflation is rolling over, just as the central bank pulls the trigger on its first rate hike in nearly 20 years . This naturally raises questions about how far above zero the BOJ’s policy rate will get. This is even more so given that the BOJ’s ability to lift rates over time isn’t just be a question of where inflation is going. It is also a question of implied, if not outright, losses on JGB holdings in the financially repressed private sector let alone in the BOJ’s own portfolio, not to mention the Ministry of Finance’s net interest rate bill.

More immediately, a persistently wide interest rate differential between the Fed and BOJ sounds plausible enough to me. It is certainly what my colleagues at Pantheon Macroeconomics are forecasting. But what about the near-term sustainability of JPY weakness? My old colleague and friend Simon White points to the risk that Japan’s significant net foreign asset position will start to shift in response to the prospect of higher domestic interest rates. If it does, even at the margin, it would be a powerful force driving the JPY higher. Simon also notes that options markets are currently offering some attractive opportunities to place a bet on near-term JPY strength. The two second charts below show that recent weakness in the JPY is consistent with the move in nominal and real yield differentials. The charts also show that yield differentials are now close to historical extremes.

Global fertility will soon be below the replacement level

In other news, a global fertility study published by the Lancet—see PDF here—has attracted a flurry of comments from demographic geeks. On the of face of it, that’s a bit strange given that the study—part of the The Global Burden of Diseases, Injuries, and Risk Factors Study (GBD) 2021—is based on data through to 2021. We have convincing anecdotal evidence that fertility has continued its decline since the beginning of the 2020s. So why spend time with this study?

For starters, having a fully up to date picture through 2021 isn’t as bad as it sounds. Global population numbers are lagging indicators, mainly because it takes a lot of time and effort to compile them, and to get a clear and empirically accurate sense of what’s going on. In addition, the study’s key message is controversial. The paper effectively conduces an advanced and updated forecast exercise for the global population, and the predictions are eye-catching. The study forecasts that global period fertility will fall below the replacement level by 2030, much sooner than predicted by the official UN medium variant estimates. The analysis also forecasts that almost all countries in the world will have below replacement level fertility by 2100, again in sharp contrast to the idea, embedded in most official forecasts, of stabilisation in period and cohort fertility at just over two children per women.

Neither of these predictions will be news to the people who have followed my work on demographics in the last few years. Indeed, I think global period fertility will fall below the replacement level as early as in 2026.